PART 5: FUNCTIONAL AND THERAPEUTIC CORE TRAINING DONE RIGHT

So far in this blog series I’ve discussed lumbopelvic anatomy, defined the core, and deciphered common daily activities. Those cover the basis for low back health and optimizing movement patterns. Now that you have the foundation, I can get into the “meat and potatoes.” In this installment, I will discuss therapeutic and functional core stability. I will discuss how to make it individualized and review common errors with popular core exercises.

The first part of selecting core exercises for you starts with the proper understanding of the responsibilities of the “core.” Stu McGill states, “Evidence and common practice are not always consistent in the training community. For example, some believe that repeated spine flexion is a good method to train the flexors (the rectus abdominus and the abdominal wall). Interestingly, these muscles are rarely used in this way because they are more often used to brace while stopping motion. Thus, they more often act as stabilizers than flexors. Furthermore, repeated bending of the spinal discs is a potent injury mechanism.” As long you understand the goals of your exercise selection then you should be ok. Is McGill saying not to do decline situps or crunches, or twists? Not necessarily. If your goal is to increase the stability of your torso, then your best bet would be to train them as stabilizers (planks, bird-dogs, anti-rotations, etc). Your understanding will dictate the effectiveness of your chosen exercises. Don’t let others sway your thinking because they are not the same as you and may have different goals. There are certain guidelines for all exercises of course, but within those guidelines lie room for interpretation based off your individual anatomy and individual goals/endeavors. Reviewing the information in installments 1, 2, 3, and 4 will help you figure out what is correct for you.

Let’s talk about some “core” exercises that performed incorrectly more often than not. Bird-dogs are a great anti-extension exercise (with some anti-rotation properties), but people have turned it into a lumbar mobility exercise lacking the full understanding of what you are trying to achieve with the exercise. You start on all fours and find the optimal lumbar position for you using the pelvic tilt. Once you pick that position, your lumbar spine and core should not move from that position. Extension should not increase, flexion should not increase, and rotation and side bending should not change either. To achieve all of these takes a lot of concentration, but will highly increase the effectiveness of the exercise. Let’s take a look:

In the first picture (left) I’m in the starting position. As the leg/arm go out you want avoid extending more or opening up the hips (middle). You want to end up with your arm/leg extended with keeping your lumbar spine unchanged (right). Clamshells are another exercise that is performed with a lot of variety. Now if you are using the clamshell to increase hip rotator strength, then you don’t have to focus on lower back position as much. If you are using the clamshell to introduce movement on top of lumbar spine stability, then the same rules apply. Lumbar spine should not change in rotation, flexion, extension, or side bending. Let’s take a look:

The first picture is my starting position and I have found my optimal lumbar spot via the pelvic tilt (left). As your leg comes up you want to avoid rotating backwards and you don’t want to lift the leg too high, which will cause your lumbar spine to rotate (middle). You want to lift the knee as high as possible without the lumbar spine moving (right). As you can see, because of my muscle length issues, my knee doesn’t go up very far. If I tried to push it higher, my lower back would rotate and I would have lessened the stability function of the exercise. Again, if I’m only going for hip rotation strength, then great no worries. However, if I am going for lumbar stability and the leg goes up too high, I’ve missed the mark. Moving on to bridges; most people tend to overextend to try and get their hip higher, especially if you have short hip flexors and lack hip extension mobility. If you incorporate heavy hip bridges into your routine, be careful. If you compensate with lumbar extension you are putting yourself at risk for an injury. Here’s what I mean:

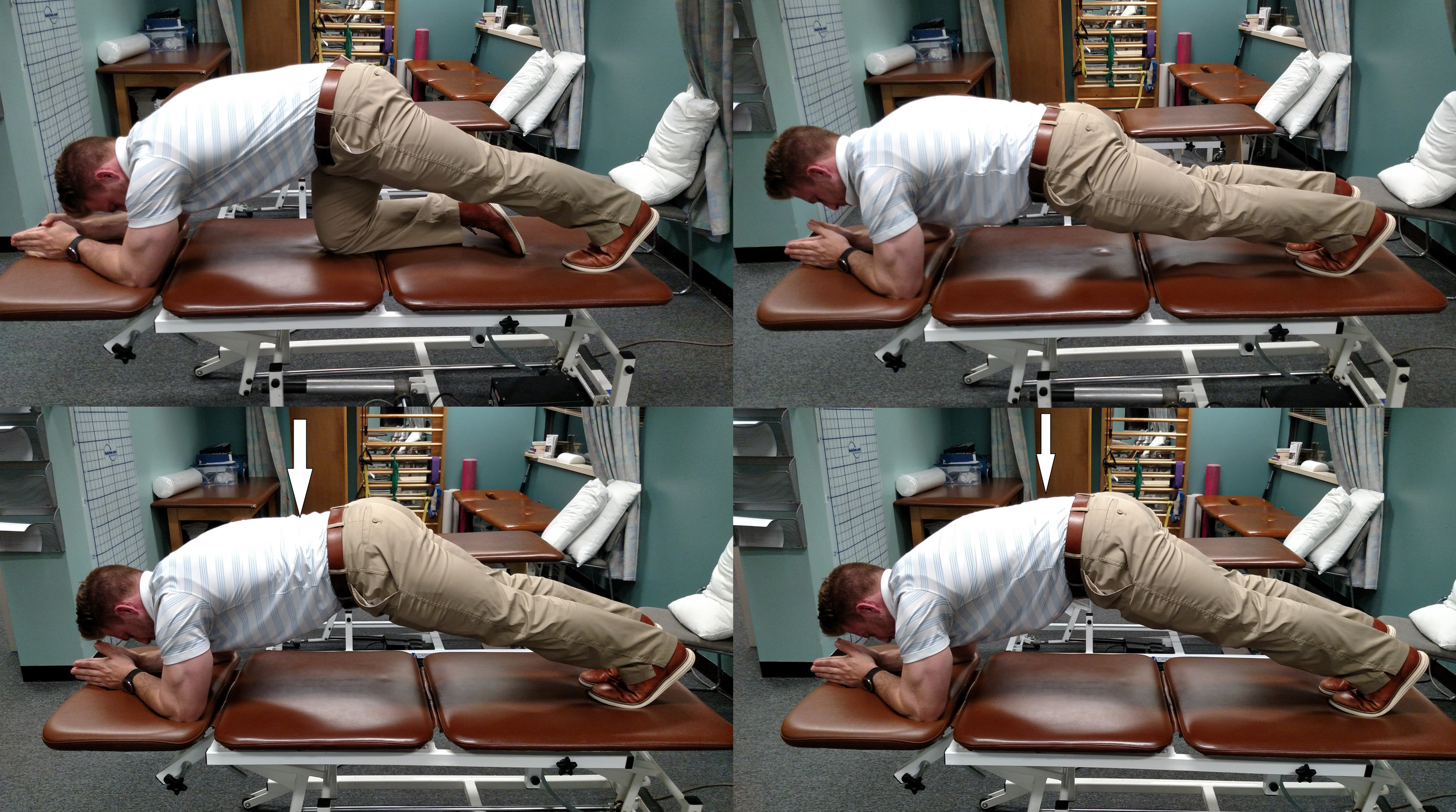

On the top left, I have found my starting position for my lumbar spine. As I lift my butt, the low back should not over extend (top right) or “roll up” bringing your low back into flexion (bottom left). It should remain in the exact spot you started in with all the movement being generated by your hip extensors (bottom right). Planks are probably the most common exercise performed incorrectly. Planks are also unique in that you must hold a posterior pelvic tilt regardless of your optimal position. If you don’t, you’ve lessened the effectiveness of the anterior core to maintain your position under heavier loads, and thus are not getting the full benefit of the exercise. To individualize the plank to every person, you have to figure out where you or your client loses the posterior pelvic tilt. You stop coming closer to neutral/parallel as soon as that happens and hold. As you progress, you will be able to come closer to parallel without losing the pelvic tilt. Here are some pictures illustrating those points:

On the top left is my starting position. Notice my hips are in a flexed position and my butt is up. This is so I can engage the posterior pelvic tilt. I engage the tilt, and start to lower towards parallel (top right). If I lose the tilt but I’m not parallel yet (bottom left), then I stop right before where I lost the tilt and hold there (bottom right). Eventually you want to work down to parallel with the proper tilt (top right). Let’s take these points and look at a rotation progression to emphasize stability and control of lumbar/core position. If performed correctly, the double overhand cable rotation/chop is a great exercise to emphasize lumbar control while the shoulder and thoracic spine rotate. If performed incorrectly, you miss the mark of lumbar control and stability and this turns into a lame full body rotation exercise and essentially becomes useless. This is how you execute the movement:

Start in the same position as the paloff press/anti-rotation (top left). As you let the weight go back towards the machine your thoracic spine and shoulders rotate slightly, but your torso, belly button, and hips should all still be pointing straight forward (not towards the machine - top right). As you pull the cable away from the machine it is the same process; your shoulders and thoracic spine rotate away, but your lumbar spine and hips stay facing forward (bottom left). You should not end up with your lumbar spine, belly button, and hips twisted the same way your hands are going (bottom middle and bottom right).

When developing a core stability program or selecting exercises to increase your core stability, you must be honest with your level of motor control (how well you can keep your lumbar position). Remember the goal of the exercises or program, you are trying to brace and stop motion from occurring in the lumbar spine and torso. Start with exercises that involve one or two joints with relatively low load/pressure and in a hook lying or quadruped position. Increase the challenge by increasing how compound the movement is (air squats), how much pressure is added (dead bugs), and how difficult the new movement is (double overhand cable rotation/chop). Let’s look at some progressions of a lumbar stability program going from rehab level to functional strength and conditioning. The exercises listed here are just examples of where I would place them for various clients depending on their ability.

The levels are arbitrary numbers demonstrating easiest to most complex exercises for core stability

- level 1

- bent knee fall outs, clamshells, balance kicks, close grip pulldowns, birds

- level 2

- squats, dogs, bird-dogs, straight arm pulldowns, paloff press/anti-rotations

- level 3

- single arm alternating cable press, single arm alternating cable pulldowns, dead bugs

- level 4

- planks, side planks, farmer’s walks, squats on unstable surfaces

- level 5

- double overhand cable rotations/chops, diagonal cable chops, cable pull throughs, ab wheel rollouts

Note there are a ton of other exercises possible; these are just illustrating an easy to complex progression. If you choose other exercises, just place them in a similar category to some of the examples to get an idea of where your selection lies.

I covered a lot of exercises above, but notice I did not mention crunches, situps or any variation, ab machines including the twisting machines. I personally would avoid these machines because I think there are better exercises that will help you reach your goal quicker. That being said, strategically placed exercises of this nature can be effective. It takes a lot of understand of the goal and how to progress it to include one of these types of exercise. For instance, decline situps are a popular exercise. There is a ton of compression on the spine from the psoas and rectus abdominus, but if you can keep the lumbar spine from going into flexion as you perform the movement then this becomes a very high level challenge to maintain your stability and core position. See what I mean about understanding the goal?

That takes care of therapeutic and functional exercise. If selected and programmed correctly these will enhance your movement patterns, make your lifts easier, and increase your low back longevity. Next week, I will talk about taking all of this “core” stuff and applying to athletics and heavy strength and conditioning.

References

McGill, S. (2010). Core training: Evidence translating to better performance and injury prevention. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 32(3), 33-46.